On 29 July 1943, as further qualification to become an ensign in the Merchant Marine Reserve of the U.S. Naval Reserve, I swore an oath to protect the Constitution. The same paper contained the words, “Duties: Engineering.” I qualified, after an exciting year at sea in all war zones and by having obtained a third-assistant engineer’s license. Lieutenant Commander Schuyler Cummings, also of the Merchant Marine Reserve and then assigned to the U.S. Navy’s Manhattan Office for Naval Officer Procurement, asked, “Why are you volunteering for active duty?”

We both knew that if I returned to the merchant marine that I would receive more than twice an ensign’s pay. I replied that I wanted the challenges such as could only be found in the engine rooms of modern Navy ships. He reacted as if I had given the most profound reason that he had ever heard. “You’ll go a long way in the Navy,” he said.

Neither one of us knew that with his acceptance of my request for active duty, a war within a war had been declared.

During the summer of 1943 the real war had a long way to go. Even though I would be instantly useful in an engine room of any ship, I was assigned for temporary duty to the Commander of the Third Naval District “while awaiting orders from the Navy’s Bureau of Personnel.” After twenty-seven days of inane assignments designed to keep me from bothering anyone, I was sent to the Subchaser Training Center in Miami. So instead of standing engineering watches in a ship, I found myself riding a Pullman in company with another new ensign and engineer from the Merchant Marine Reserve, John Martin Francis Aloysius Doyle. John was expressing the same disappointment in his Bronx accent that I was mouthing off in Brooklynese, “How do I get out of this chicken outfit?”

The first real shot of the war within the war was fired by the Navy. John and I believed that we would be assigned to the turboelectric school at the Center as preparation for engineering jobs in new destroyer escorts. Instead we found ourselves in a course for ninety-day wonders who were being trained in ship handling, navigation, communications, etc. In our minds, exposure to leprosy was preferable.

In an attempt to prevent dilution of our engineering only culture we beat a path to the Center’s executive officer, a commander. He listen for less than a minute, interrupted, and dismissed us with the observation that the course was only for five weeks and that it was easier for us to attend it than it was for him to arrange our transfer to the turboelectric school. Thus the return fire to the Navy’s opening shot was a Brooklyn/Bronx pact that was conceived in Miami; we vowed to fail all subjects except engineering administration.

Those who failed two or more subjects were brought before a board that consisted of the Center’s commanding officer, a few other captains, and the executive officer. Since we were obvious coconspirators John and I were ordered to appear together. While the captains glared at us as if they knew that we were prisoners taken during the war within the war, the exec shuffled through our files, looked up, and demanded, “How did you two get in the line-officer course?”

I was stunned. How could he have forgotten us so soon? But John Martin Francis Aloysius Doyle wasn’t stunned; he was prepared. His feet moved a bit apart. He then leaned back from his waist, tilted his head to one side, and in a Bronx nasal whine said, “Why don you know commander? We asked you dat da foist day we got here.”

The other officers, including the skipper, almost gagged trying to stifle laughter that could only be at the red-faced exec’s expense. We were instantly dismissed.

Because of the many officers coming and going, the Bureau of Personnel forwarded blank orders and left it up to the Center, presumably the exec, to fill in names. Within a day after our appearance before the board, John was sent to the USS SALT LAKE CITY (CV 25) that was in the Western Pacific, had already been in a battle, and was expected to see more combat. I was sent to the turboelectric school wondering if Doyle’s orders were a consequence of his mouth.

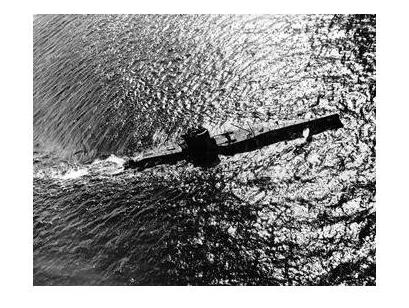

After another four weeks the Navy fired the second salvo of the war within a war. I was ordered to USS EAGLE 19 (PE 19), the oldest of the eight subchasers remaining that had been built by Henry Ford in 1918!

Also, most operations assigned to EAGLE 19 were antisubmarine-training exercises with 1919-vintage R-boats. I felt like I had been put in a time machine and sent back twenty-four years.

EAGLE 19 didn’t have a reciprocating engine, but its power plant was just as remote from a turboelectric installation. The machinery advances that would challenge me professionally had passed it by. In addition, EAGLE 19 could not have more than five officers in its complement. For sure there would be pressure for the engineer officer to qualify as an officer of the deck. Thus my orders, in a de facto sense, ordained that the war within the war that the Navy was not yet aware of, would continue.

On 1 December 1943, with fifteen weeks and four days totally wasted, I reported to ancient, rivet-rattling, notorious-for-extreme-rolling USS EAGLE 19 that operated out of mosquito-bitten, pelican-pooped-on, fungus-producing Key West. No international convention had established rules for the war within the war. The Navy had resorted to torture.

***************

Copyright © 2005 (text only) by Louis D. Chirillo