“I enjoyed your story about how you introduced tea bags to Australians thirty-years before I created Cooney Sales Company,” said Paul Cooney, a food sales expert. “But,” he added, “You said that was one of two such achievements. What was the other?”

The second occurred four months later on the opposite side of the world in Wales. USAT URUGUAY, from an anchorage in Scotland’s Firth of Clyde, discharged troops into small paddle-wheel vessels for their transfer to waiting trains in Gourock, and then steamed down the Irish Sea to Swansea arriving on 17 August 1942. Swansea was then something to behold.

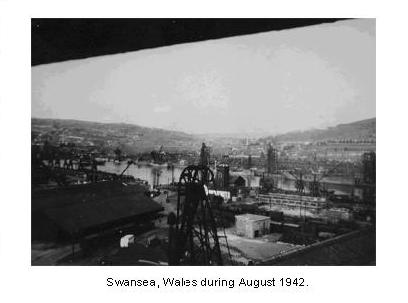

The docks, which had great military value and would have been difficult to restore had they been bombed, sustained no apparent damage. The barrage balloons hovering over and the likelihood that at least one ship would have antiaircraft guns, seemed to have caused the Luffewaffe pilots to look elsewhere for prey. As a consequence business districts and bedroom communities were pulverized in and for miles around the valley leading to the waterfront.

Since the tide in the Bristol Channel is extraordinary, over thirty feet, the docks were located inside an approximately twenty-acre basin that was accessible only through a lock, that is, a canal-like enclosure with a gate at each end. In order to enter, a ship had to pause in the lock while the gate behind was closed. Then the water level within the lock was adjusted to be equal to that within the basin, and the inner gate was opened. The water level inside remained steady while outside the surface was moving up and down thirty or so feet every day. Thus, unloading and loading ships inside was greatly facilitated.

Because URUGUAY had an eighty-foot beam and the lock was only eighty-four feet wide, and since entry by large ships was made difficult by the presence of a sea wall that provided some protection whenever there were gale-driven seas, A.P. Spaulding demonstrated that he was a master among shipmasters. There were no tugs. He brought the 20,000-ton URUGUAY into the lock assisted only by two Welshmen in a rowboat who passed ashore the bitter end of a hawser.

URUGUAY had called at Swansea for the purpose of unloading a cargo of GI beer that was in the bottom of the forward hold. It was not the beer that I promoted as a food product; it did not need any promotion.

I suppose it was the first beer brewed and canned with generic labeling. As all other army issues, each can was painted olive drab and printed over with a brief identifier. The cans were packaged twenty four to a cardboard case. The cases were stacked on pallets, as was most break-bulk cargo in those days, and there were 144 cases per pallet, that is, there were when they were lifted from the hold. Welch stevedores operated URUGUAY’s winches and transferred the beer to waiting lorries. The discharge of the beer cargo progressed day and night.

Because of the blackout, the stevedores worked in the lower hold with barely sufficient light provided by feeble battery-powered torches. Those who operated the ship’s main-deck winches relied on whistle signals from the dark lower hold and from the lorries in the blackness on the pier alongside.

Since the Welshmen were of the salt of the earth, they readily cooperated when a brother worker from the ship’s crew, standing on the ‘tween deck below, whispered, “Hey mate, stop the next pallet here for a few seconds.”

Thus, depending upon extended-forearm strength many pallets were lightened by one or two cases.

At dawn the next day the authorities didn’t need Sherlock Holmes to explain to them that more than URUGUAY’s crew and naval armed guard were into the cargo of beer. The twenty-acre basin seemed to be covered with floating cans. Professional drinkers among the longshoremen and the lorry drivers had to have assisted.

I always worked day work in port. Therefore my only ventures ashore were following sunsets. After a number of forays into blitzed Swansea with my soon-acquired owl-like night vision I discovered a still-standing blacked-out pub that I had not yet explored. The goings on in the brightly-lighted inside was a kaleidoscope of drinking, singing, and laughing by mostly middle-age and older working-class folks, as if the effects of what must have been like Dante’s Inferno did not exist around them.

Two things stand out in my memory. Some of the women believed that touching a mariner’s gold buttons would bring good luck. Unfortunately only those who seemed to be grandmothers were superstitious. Also, a door across the room from the bar was labeled Gentlemen. The door led into a dark alley where a section of the exterior wall was reserved accordingly. Gentlemen could see the stars but not their shoes.

In just about every British port the way back to the ship seemed to be the same; find Queen Street and walk downhill. But I was in luck that night, while looking for Queen Street in the inky-black rubble a cabbie found me.

One had to see the taxi to believe it. It wasn’t like the cabs in New Zealand that had charcoal burners for generating the coal gas that was burned in place of petrol. Once during a ride in Wellington the Kiwi cabbie sent two of us into hysterics when he said, “I have to stop a mo lads, to put another log on the fire.”

In Swansea each cab was fitted with a large gas bag on its roof; it seemed as if a small blimp was about to effect lift off. Every few hours the taxi had to go to a depot in order to fill ‘er up with stove gas.

We blimped through the black destruction and with the driver employing the navigating capabilities of a salmon seeking the stream of its birth, found Queen Street. We headed downhill and wended our way through the cluttered dock area. Then I discovered that I didn’t have enough to pay for the ride. The cabbie wasn’t upset and readily agreed to wait while I went on board with the intent to wake a shipmate and borrow a few shillings.

I soon learned that those who I would dare disturb were broke. Due to a plan hatched to resolve my dilemma, I found myself once more in the food promotion business.

Returning from the boat deck to three-decks below where the gangway was located, I had to pass the night pantry. The pantryman was sympathetic and told me to take whatever I needed. So for the purpose of promoting a product of General Mills, Inc. and as a means to an end, I picked up an unopened case containing individual breakfast-size packages of Kellogg’s corn flakes, went back down the gangway, and started what turned out to be unnecessary barter negotiations. When he saw the box the Welshman became ecstatic.

I explained, “I could not borrow any money so I brought you some corn flakes.”

He had never heard of them and in response to his query I added, “Corn flakes are a breakfast cereal.”

He then asked, “How do you eat them?”

I was pooped to say the least and without thinking I said, “Put them in a bowl; add milk and sugar.”

“Oh,” he exclaimed despondently.

I had momentarily forgotten the severe rationing then in its third year. Surely, except for the U.S. entry into the war eight-months before, Britain would have been brought to her knees because German U-boats had reduced the necessary import of food to a trickle. The cabbie was not likely to have tasted milk in a long time. What little was available was reserved for children and for him, sugar no longer existed. In addition, the latest war news was not encouraging. At that very moment Canadians were being slaughtered in the disastrous raid on the French coast at Dieppe just 240-miles away.

While feeling sorry because of my blunder I said, “I’ll go back and exchange the corn flakes for something else. Perhaps I’ll find some sardines.”

Not willing to let go of a bird in the hand, the Welsh cabbie responded, “The corn flakes will do. I’ll find a way to eat them.”

***************

Virtually the entire city, located in a valley leading to the waterfront, was in ruins. Photo shot from between the inner and outer stack from just under the stack cap.

***************

“The sixth blitz on Swansea and its last raid suffered was on 16 February 1943. A few bombers dropped flares some time after 10:00 p.m., before circling the town to release their load of 32 High Explosive bombs and a substantial amount of incendiary bombs. The raid lasted a relatively short 30 minutes, but killed 34 people, injured 110 and caused considerable damage to residential houses and shops.”

BBC

***************

Copyright © 2005 (text only) by Louis D. Chirillo