I was more or less indoctrinated before being assigned to a ship. I had entered the U.S. Maritime Commission Cadet Corps on 20 January 1942, a month and a half after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

A week later I was in a work party that moved out of Fort Schuyler, crossed Long Island Sound in a motorboat, and helped prepare the Chrysler estate for what was the fledgling U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. Our first job was moving the furniture out of Mrs. Chrysler’s former bedroom and moving in upper and lower bunks for twelve cadet midshipmen. Cadet designated our title as apprentice merchant-marine officers. Midshipmen denoted our Naval Reserve status.

When Lieutenant Commander Lauren S. McCready of the U. S. Maritime Service, learned that I knew my way around lower Manhattan, he employed me as his driver. He was busy getting permission from steamship company executives to collect various items, then being removed from passenger ships, that would be useful at the Academy. During one such day, 9 February 1942, we watched the fire that destroyed the huge French liner NORMANDIE.

Other days of my so-called indoctrination for a career at sea included being trucked to Brooklyn’s Bush Terminal as one of a work party assigned to load Lieutenant Commander McCready’s booty. I was sidetracked one day to attend my high-school graduation ceremony, and I spent one week, supposedly on mess duty. Instead, I mostly dealt with food-delivery men as a non-German speaking translator for the Academy’s non-English-speaking German cooks who, as a security measure, had been removed from ships operated by U.S. Lines.

In addition, my mechanical-drawing skills acquired in high school, were exploited for the preparation of floor plans for a number of the nearby Gold Coast mansions, including Sinclair’s and Schenk’s, that ultimately became part of the Academy.

After five such weeks, I was ordered along with William L. Summers, another cadet engineer, to report to Lieutenant Harold E. King, U.S. Maritime Service, in an office located in the heart of the substantial ocean-shipping community that then dominated the lower part of Manhattan. Lieutenant King was informed of ship arrivals and departures and was responsible for assigning cadets to ships for one-year apprenticeships. Due to war demands, later on that period was reduced.

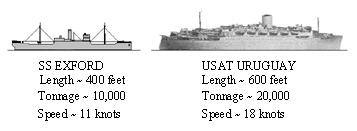

Bill was older than my eighteen years and as our meeting with Lieutenant King disclosed, Bill seemed to be savvy about merchant ships. After greeting us, Lieutenant King said, “Chirillo, you are going to EXFORD. Summers, you are assigned to URUGUAY.”

Lieutenant King started to record the assignments when Summers interrupted, “Can we swap?”

I have no idea how Lieutenant King determined who went to what ship. Perhaps because he didn’t want to trifle with fate, he made assignments in alphabetical order. He knew that merchant-seamen casualties were already occurring at an alarming rate. Lieutenant King looked a bit perplexed and then he said to Summers, “It’s OK with me if it’s OK with him.”

Having no reason to object, I agreed. I never asked, “Why?”

Afterwards when I learned more, a motive came to mind.

I think that Summers knew that URUGUAY was a passenger liner converted to a troopship and that the Navy had been appropriating such vessels. When taken by the Navy, officers on board who were in the Naval Reserve were ordered to active duty and were retained on board. Cadets who were also midshipmen in the Naval Reserve, were included.

At that time most of us preferred the merchant marine to the Navy. Summers probably knew that EXFORD was a Hog Islander, that is, one of the cargo ships built to a standard design during World War I just as Liberty Ships were built during World War II. There was no likelihood that the Navy would want a Hog Islander. But, URUGUAY was allocated to the Army as a troop transport and Moore-McCormack Lines continued as the operator.

I never met Bill Summers again, but I know he survived the war. History books describe a bit of what he experienced.

EXFORD was bound for North Russia via an Arctic convoy route. From the time of our visit with Lieutenant King until 29 June 1942, EXFORD loaded cargo, managed a slow voyage to Halifax, joined convoy PQ.17, was holed by heavy ice, and turned back to Reykjavik, Iceland for repair. Thus, Bill was spared the massacre that is described in David Irving’s book, The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17.

During that same period, URUGUAY steamed to Panama, Bora Bora in the Society Islands, Auckland, Melbourne, Wellington, San Francisco, and returned to Auckland. When ice-damaged EXFORD was heading for Reykjavik, URUGUAY was approaching the Panama Canal after having completed two voyages across the Pacific Ocean.

Then I heard that when URUGUAY was transporting troops to the United Kingdom, Bill Summers was in another ship that was torpedoed and sunk while part of another convoy bound for Murmansk. I also heard that survivor Summers spent some weeks in Scotland waiting for passage back to the United States. During that same period, in URUGUAY, I went to Glasgow, Swansea, and Liverpool in the British Isles, and, during the Allied Invasion of North Africa, to Mers El Kébir, Algeria.

Bill Summers and I might have walked by each other on a blacked-out Glasgow street. Had we then met, we would have exchanged sea stories and I would have reminded him, “You are the one who asked, ‘Can we swap?'”

***************

***************

“What unions feared most was that war necessity might be manipulated to erode or demolish all the gains they had won for their numbers in years of bitter strikes and struggle.

“The strikes had prevailed over ghastly conditions: meager and often rotten food; no mess hall; drafty forecastles crowded with skimpy, vermin-ridden bunks and bedding; filthy toilets; crude cold-water spigots; and buckets for lavatories.”

p. 174, The U.S. Merchant Marine at War, 1775-1945, edited by Bruce L. Felknor, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1998.

***************

“The fact was that the first part of 1942 was a very dark time indeed. The news was nearly all bad. U-boats were sinking American ships with terrible regularity. The Japanese had smashed our best fleet in Hawaii, defeated our best general in Luzon, destroyed Britain’s finest warships, captured her most impregnable fortress, and seized a huge empire in one incredible swift campaign.”

p. 149, Picture Historyof World War II, C.L. Sulzberger, American Heritage Publishing Co., 1966.

***************

“In the first four months of 1942, 87 ships were sunk off the U.S. Atlantic coast.”

p. 197, Picture Historyof World War II, C.L. Sulzberger, American Heritage Publishing Co., 1966.

***************

Copyright © 2005 (text only) by Louis D. Chirillo