Some of the August 1942 nights in blitzed Swansea were darker than others. Believing that four eyes are better than two I went ashore with Cadet Earl Frank. We often found ourselves in conversations with people we could not see. In a way it was like walking through a minefield. For example, during a moonless evening a shipmate from USAT URUGUAY had been attentive to a Welsh maiden, so he thought. Quite by chance her husband walked by, overheard the conversation, and swung at where he thought the Yank was standing. Thanks to the darkness, the American Romeo was able to slink off unharmed as he left a loud argument behind.

Earl and I thought that we were being prudent when we waited for a bit of moonlight before we approached a cute pair about our ages who introduced themselves as sisters. They had just finished work and were lingering in Swansea in order to absorb some of the excitement before they caught a bus for home. They were really in luck; we big spenders took them to dinner. It was a stand-up place that served recognizable fish and chips in cones made from newspapers. The frying oil smelled of continuous use since Germany attacked Poland three-years before. We didn’t stop spending there.

In what seemed like a moment of daring for them the girls accepted our invitation to go to a movie. The theater might have been elegant had not most of the roof been blown off. Showing a film there was a rare exception to the blackout.

Afterwards the sisters expressed fear about going home. There might be a drunk among the few passengers on the late bus to The Star, an intersection of five roads. From there they would have to walk unescorted for about a mile through a region where there were no houses.

As if that wasn’t scary enough, they were terrified about having to confront their father who wanted them home hours earlier. “If you accompany us home,” they said, “you would have plenty of time to walk back to The Star and catch the bus back to Swansea.”

We understood that the outward-bound bus, after our stop would continue to the end of its route and return to Swansea via The Star. As spirited and brave mariners, we did not deny the distressed damsels.

We arrived at The Star about ten and there was enough moonlight for us to see that it was indeed open country and that the five unmarked narrow cobblestone roads looked alike. We started along one road as the shrouded lights on the bus quickly disappeared on another. There was an embankment on both sides leading down about four feet to uncultivated land. Fog patches were already forming and clouds caused intermittent moonlight. Earl and his date walked ahead and disappeared into the gloom.

The British employ two words for such desolate expanses. I imagined that Sherlock Holmes was searching the heath for clues in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s latest thriller, The Case of the Marine Engineers Who Vanished from the Moor. I was having second thoughts about gallantry.

After a few minutes, as I was thinking that I would not be surprised to hear the howling of a hound, I heard something else just as chilling. Heavy shoes were making increasingly loud sounds as if anger was being pounded against the cobblestones. My date momentarily froze as she whispered, “My father!”

Quickly, she pulled me off the road and we laid face down on the embankment. Obviously she had prior such experience, because she seemed to be confident that the approaching apparition would not look sideways. I looked up just in time to glimpse the disappearing man of considerable bulk.

We climbed up to the road, walked a bit faster because I was eager to find Earl, passed a graveyard, and soon arrived at a small stone house. There were no other houses. Earl and his companion arrived a few minutes later. When I asked where they were when the eerie sight went by, my wide-eyed buddy replied, “Behind the wall in the graveyard.”

Earl and I weren’t enthused about going back to The Star. The sisters assured and reassured us that their father would only wait for the next bus from Swansea. By the time we returned to The Star he would have headed off on another road to an after-hours pub where he would spend at least until midnight drowning his anger. We embryo marine engineers, thus fortified with assurances, started back while swearing never to get so far inland again.

We didn’t know then that the evening had only just begun. No bus returned to The Star!

A bit before midnight we picked a road and hoped that it was the one that would lead us to Swansea. We saw signs of life only three times. One was early in our trek when a lorry rumbled by. For whatever reason, the driver did not give us a lift. The second was across another moor where we could see a fiery glare through shrapnel holes in the sheet-iron wall of a foundry. The third was just before dawn when a policeman spotted the lighted match we were using to illuminate a still-standing street sign. He led us through the ruins to the docks where we arrived on board URUGUAY just in time to start work! By then it seemed that we had walked to Scotland.

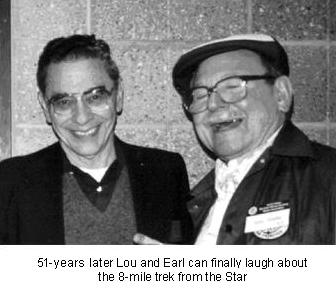

Earl and I eventually learned that we had hiked eight miles from blitzed Morristown to blitzed Swansea. Somewhere on the heath that night, chivalry died.

***************

***************

Glasgow

“Most of the workers tenements which had stood in an endless row along the inner side of the Dumbarton Road had been blitzed to rubble by the Lufewaffe. In both directions, in the gathering dust, were ships, some of them gaunt skeletons, some nearly completed, and others grim veterans up from the sea to heal their wounds of war. Masts, funnels, derricks, and gantries fringed the river like burnt cypresses beside the Stix, while above them, ghostly in scudding fog, barrage balloons tugged swaying at their cables, waiting for the bombers which now so seldom came.”

The Canny Mr. Glencannon, by Guy Gilpatric, E.P. Dutton,New York, 1948.

***************

Copyright © 2005 (text only) by Louis D. Chirillo